I'm in the process of gathering images for submission for publication. You might want to make a collection just to show arown, to archive because they are important images to you, or to impress a gallery owner. Regardless, there is a process involved in selecting and making images for said portfolio that might be interesting to discuss.

The first question is what images to include. I decided that I'd include only images from my fall holiday to Vancouver Island, many of which images have graced my blog, as recently as today. I ended up with about 20 images. A few just didn't fit (one was a mountain top from a plane, covered in snow - it was the only snow image and really didn't fit. A couple of other images weren't as strong as the others and I felt they dragged down the portfolio quality by their inclusion. Take it as a given that you will be known by your weakest images, that if the person you are trying to impress or persuade gets a chance to see a weak image before a strong one, you are doomed, that if the weak image follows the strong one, it drags down the strong one.

So, unless you have a strong reason to include all suitable images, only include your best in any portfolio. Do remember though that this may not necessarily be a collection of your favourites, it would be perfectly reasonable to include good images that others like yet which aren't your favourites.

That said, BEWARE, if you include images you really don't like (no matter how much others rave about them), they are sure to be chosen for the cover picture, the show brochure, or some other featuring which means you will be known by and for this image - if you don't want to be permanently and exclusively known for this image, then don't tempt the editor, gallery owner or whoever. You have been warned!

I had already decided to choose only black and white images - I had particular magazines in mind. it would be rare for it to be appropriate to include both black and white and colour. I personally don't like looking through books or magazines that mix colour and black and white within one article or section. Rarely is printing ideal for both black and white and colour in the same magazine or book (though Phot'Art does a pretty good job).

I now had about a dozen images for my portfolio. Half of them were driftwood images which meant that the other shots seemed like poor country cousins.

I now have to decide - do I limit the portfolio to just driftwood images? Definitely possible, though one wonders just how many driftwood images any one person would want to look at. Still, for publication, the editor is going to pick his or her favourites so only a selected few will grace the pages in likelihood. Do I then pad the collection with some good driftwood images from other shoots? If the definition of the collection is driftwood, or even deadwood, how about including an image of a burned stump in a farmers field shot on 4X5 many years ago - or a mostly dead tree within a park locally, or even a stump in a neighbours yard, or how about an image of a tree trunk (quite healthy) but with an old sawed off branch wound slowly healing?

Boy, now I'm really getting away from my original intention which was to show in a single portfolio, what I was able to find on a one week trip. I guess I could edit out most of the driftwood pictures and include perhaps three of the best, but the portfolio is getting a bit small - again editors like choices, Ideally I'd like to be able to show 12 - 15 good images and if the editor asks for more, have a backup of at least the same number again of strong alternate images.

Perhaps this weeding and choosing process is already familiar to you. it's not trivial. To a significant degree you are trying to guess (usually with little information) what the person is likely to want, be interested in, or select for sale or publication.

Some time ago I took to the local Glenbow Museum a number of landscape photographs as well as some old industrial images of historical significance (new images, old historical artifacts). Oddly, this museum known for it's interest in local history, rejected every single one of the industrial images - they wanted pretty post card type images only - go figure. Presumably they know what sells but it would have made sense to supply them only with 'historical' images which would almost certainly have resulted in outright rejection.

In the end, if the portfolio is for publication, I would place consistent theme above every other selection criteria, closely followed by the power of the individual images. One could include other images which flesh out the story (if there is one), but that rather depends on the kind of magazine you are looking to submit to. A travel magazine might well want a few powerful images and others to fill out the story, a photographic magazine probably wants to print only powerful images.

A gallery might not need a theme, particularly if you are already known - eg. retrospectives, best of collections etc., but for the most part even here a consistent theme is easier for them to manage - they don't want industrial mixed with landscape, black and white mixed with colour. Even abstract vs. literal landscapes can be an issue.

In the end, I still haven't decided exactly what to include in the portfolio. Hell, I haven't decided on what magazine yet and still haven't convinced myself the images are good enough to submit. I guess I'll be staring at them for a while yet, refining the portfolio and doing my best to realistically evaluate the quality of the images.

Arguably the worst that could happen is that the images get rejected out of hand and I'm free to submit again in the future with different images, but I don't like the idea of sending out images that are not as strong as possible - those images are me, warts and all.

Wednesday, February 28, 2007

Tuesday, February 27, 2007

But Does It Work

I was quite excited about this image when I found it but even then I had difficulty framing it - it seemed that with the stump occupying three of the four quarters of the image, it was a bid odd with that relatively bare fourth quarter. I made a couple of stabs at making an image out of it when I returned from the trip, wasn't impressed and forgot about it. Looking over old files for a magazine submission, I decided today to have another 'kick at the cat'.

I quite like it but can't decide if I have simply 'talked my self into it' and am deluding myself.

This is a perfect example of an image that needs to hang on the wall for a couple of weeks. If I still like it after that, then it's a keeper, if by then I can't stand it's asymetry and what not, well down it comes and off to the 'might have been, almost could have done, not quite made it' bin.

I don't suppose it would surprise you to know ths bin is larger by far than my 'darn, that's a nice image' folder.

Success Is Fleeting

In recent entries I talked about dealing with disappointment, then went on to discussing turning rejection into success and Joe succinctly pointed out that many of us don't want to run a small business with all it implies.

This raises the whole issue of what is success, how do you achieve it and what happens then.

I have bad news, success is fleeting. No matter what your personal definition of success is - getting published, having your own show, selling a print for more than $100, winning a prize in the local camera club, whatever it might be, once you achieve that goal, your definition of success automatically changes, now you need a show in a major gallery, or you up the print price success point to $500 or you decide magazine publication is not enough, now you need book publication, or you have to win a national competition.

I suspect it's universal human nature to want to achieve the next goal, forgetting the achievement of the recent goal almost as soon as it's achieved. If I'm wrong do let me know your secret to being satisfied with the goals you have already reached.

If I'm right, then you too need to stop and appreciate the successes you have had. Perhaps they are small - a friend admiring a photograph, but we need to take our successes when we can.

Of course, if we never let anyone see our work, if it hides in old paper boxes, who's to appreciate it?

Sometimes it's not necessary to move on to new goals, rather, to repeat occasionally goals already achieved - get a print in the readers section of a magazine - well done. Perhaps you should submit again. Would life really be that bad if you occasionally had an image printed, yet never published a book. Many who haven't had an image published, ever, in any form, would think you crazy if you weren't happy with this much success.

It doesn't hurt to have higher goals, so long as we don't discount the lesser successes we continue to have.

This raises the whole issue of what is success, how do you achieve it and what happens then.

I have bad news, success is fleeting. No matter what your personal definition of success is - getting published, having your own show, selling a print for more than $100, winning a prize in the local camera club, whatever it might be, once you achieve that goal, your definition of success automatically changes, now you need a show in a major gallery, or you up the print price success point to $500 or you decide magazine publication is not enough, now you need book publication, or you have to win a national competition.

I suspect it's universal human nature to want to achieve the next goal, forgetting the achievement of the recent goal almost as soon as it's achieved. If I'm wrong do let me know your secret to being satisfied with the goals you have already reached.

If I'm right, then you too need to stop and appreciate the successes you have had. Perhaps they are small - a friend admiring a photograph, but we need to take our successes when we can.

Of course, if we never let anyone see our work, if it hides in old paper boxes, who's to appreciate it?

Sometimes it's not necessary to move on to new goals, rather, to repeat occasionally goals already achieved - get a print in the readers section of a magazine - well done. Perhaps you should submit again. Would life really be that bad if you occasionally had an image printed, yet never published a book. Many who haven't had an image published, ever, in any form, would think you crazy if you weren't happy with this much success.

It doesn't hurt to have higher goals, so long as we don't discount the lesser successes we continue to have.

Sandisk Read Only Memory Cards - the Future?

Several sites are announcing the production of read only 'matix' memory cards by Sandisk. They imply the cards will be cheap enough to beome the new 'film' and talk of lasting 100 years.

If this turns out to be true, it really is a huge breakthrough. Considerably smaller than a 35 mm. film cannister and probably holding a lot more images, if the price really is reasonable and if the technology really is both reliable and archival - we could well see a drastic simplification of backups - you'd simply copy the cards to your portable drive or laptop or home computer, then file away the card for a rainy day.

Of course in one way it would spoil one of the advantages of digital in that it costs nothing to experiment, to give yourself several images from which to choose and could make shooting 10 images as you adjust focus for future blending or 24 images for subsequent stitching problematic.

With a 1D camera, they hold both CF cards and SD cards so perhaps you could save all images to one card and 'burn' the good images to the read only memory card. It would mean doing the editing in camera rather than later, but with the 3 inch LCD and magnification in the new cameras, that might be practical. It would leave the other cameras in the lurch though.

One wonders if what will happen is that the price will be low enough for use in special circumstances but not for routine shooting - only time will tell.

Monday, February 26, 2007

Canon 1D3 and What It Bodes for a 1Ds3

I have no use for a high speed camera like the 1D series but I have to say the changes in the newest model bode well for an upgrade to my 1Ds2 - no announcements but if it has some of the features of the 1D3 (and why wouldn't it), I'd sure be looking to find some money...

3 inch LCD screen with live view and magnification for critical focus - sounds good to me. I have a really tough time focusing with my 90 ts-e when tilting and purchased the magnifying right angle finder which helps somewhat, this sounds a lot better.

I really like the idea of composing on the LCD - something I'll address in more detail in a future entry.

Self Cleaning Sensor - what's not to like?

Better Auto Focus - not a biggie for me most of the time, but sometimes...

There's a whole list of other improvements geared more to rapid shooting and action shots and which may not move over to a 1Ds3.

There had been talk of amalgamating the two lines, the D and the Ds series but you can see that this hasn't happened this time and reading the details you can see why - it took 2 digic 3 processors to handle the 10 frames a second of the 1D3, if as is rumoured, the 1Ds3 has 22 mp, then the only way it could keep up would be to have a full frame mode and a crop mode (a la D2X) but that creates viewfinder issues and the pixels would be smaller so I can see why Canon has gone the way they have.

3 inch LCD screen with live view and magnification for critical focus - sounds good to me. I have a really tough time focusing with my 90 ts-e when tilting and purchased the magnifying right angle finder which helps somewhat, this sounds a lot better.

I really like the idea of composing on the LCD - something I'll address in more detail in a future entry.

Self Cleaning Sensor - what's not to like?

Better Auto Focus - not a biggie for me most of the time, but sometimes...

There's a whole list of other improvements geared more to rapid shooting and action shots and which may not move over to a 1Ds3.

There had been talk of amalgamating the two lines, the D and the Ds series but you can see that this hasn't happened this time and reading the details you can see why - it took 2 digic 3 processors to handle the 10 frames a second of the 1D3, if as is rumoured, the 1Ds3 has 22 mp, then the only way it could keep up would be to have a full frame mode and a crop mode (a la D2X) but that creates viewfinder issues and the pixels would be smaller so I can see why Canon has gone the way they have.

Sunday, February 25, 2007

Turning Failure Into Success

My entry on disappointment seemed to touch on a number of readers and fellow strugglers. I wonder if we can use failures to become successful. I think we can take it as given that simply struggling on without a change in strategy, technique or outlook is unlikely to result in dramatically more success than we have had up to this point.

They say that 9 out of 10 new businesses fail. A bit discouraging, but...

Ever note how many new restaurants don't last long and you could have told them why - surly or slow service, cold food, poor selections etc. etc. What percentage of restaurants fail because the food is bad - my bet is that those failures are a small fraction of the restaurants that go under. The others fail because in rushing to become a success, they forget crucial details which almost anyone could have pointed out, but were overlooked by the new owners none the less.

Sounds a bit like my portfolio for Review Santa Fe - had I spent a bit more effort reading the criteria - it would have been clear that even though they didn't REQUIRE a unified portfolio representing a single project, that was what they were looking for - who's to day whether I'd have had any success within those limits, but it's fairly clear that in hind site, not following those hinted limits did in fact doom my entry.

This suggests to me that perhaps we fail not for lack of talent, but rather for lack of careful analysis of needs, refusal to accept outside advice from those who have gone before us, and possibly simply for lack of a good business plan.

A good business plan - for fine art photography - surely that smacks of trade, not art, of more tricks than skill, of rules rather than imagination? Maybe, but that might turn out to have a lot more to do with our lack of progress than outright creativity.

Could it be that we should save our creativity and imagination for the artwork itself while relying on expertise and experience to guide us in the business part of our work.

Let's face it, we can create wonderful images, but if no one ever sees them, or if they are presented poorly, or if the wrong people see them, or if our pricing is wrong, or any number of other business decisions is made in ignorance, then how are we going to succeed?

Creative people are often not organized people. Perhaps the few creative people who are successful are the ones with the best organizational skills, not necessarily the best photographs. Perhaps it's their energy level which makes them lug their portfolios to more galleries, send off to more magazines and promote their work to more potential clients than those of us who stay home agonizing over whether we're 'good enough'.

Perhaps we need to think of the business part of our photography not as an unpleasant task, to be avoided when possible, with the less time spent dwelling on it the better, rather to think on it as a military campaign, requiring planning and effort and dedication.

Rather we think of the business part of photography as the 'main event', as our skills and creativity as simply tools to be used in the business.

I understand from professional photographers that they spend anything from 5:1 to 10:1 time promoting their work vs. photographing.

If all of the above gives you heartburn and makes you angry, then perhaps you aren't ready to become a photography business, and you need to rethink your definition of success.

We don't after all, have to define your success by sales figures, number of publications, web site visitors or other such measures. But, if we do decide that this is the measure of our success, then we are not only going to have to accept the business method, we are going to have to worship it.

They say that 9 out of 10 new businesses fail. A bit discouraging, but...

Ever note how many new restaurants don't last long and you could have told them why - surly or slow service, cold food, poor selections etc. etc. What percentage of restaurants fail because the food is bad - my bet is that those failures are a small fraction of the restaurants that go under. The others fail because in rushing to become a success, they forget crucial details which almost anyone could have pointed out, but were overlooked by the new owners none the less.

Sounds a bit like my portfolio for Review Santa Fe - had I spent a bit more effort reading the criteria - it would have been clear that even though they didn't REQUIRE a unified portfolio representing a single project, that was what they were looking for - who's to day whether I'd have had any success within those limits, but it's fairly clear that in hind site, not following those hinted limits did in fact doom my entry.

This suggests to me that perhaps we fail not for lack of talent, but rather for lack of careful analysis of needs, refusal to accept outside advice from those who have gone before us, and possibly simply for lack of a good business plan.

A good business plan - for fine art photography - surely that smacks of trade, not art, of more tricks than skill, of rules rather than imagination? Maybe, but that might turn out to have a lot more to do with our lack of progress than outright creativity.

Could it be that we should save our creativity and imagination for the artwork itself while relying on expertise and experience to guide us in the business part of our work.

Let's face it, we can create wonderful images, but if no one ever sees them, or if they are presented poorly, or if the wrong people see them, or if our pricing is wrong, or any number of other business decisions is made in ignorance, then how are we going to succeed?

Creative people are often not organized people. Perhaps the few creative people who are successful are the ones with the best organizational skills, not necessarily the best photographs. Perhaps it's their energy level which makes them lug their portfolios to more galleries, send off to more magazines and promote their work to more potential clients than those of us who stay home agonizing over whether we're 'good enough'.

Perhaps we need to think of the business part of our photography not as an unpleasant task, to be avoided when possible, with the less time spent dwelling on it the better, rather to think on it as a military campaign, requiring planning and effort and dedication.

Rather we think of the business part of photography as the 'main event', as our skills and creativity as simply tools to be used in the business.

I understand from professional photographers that they spend anything from 5:1 to 10:1 time promoting their work vs. photographing.

If all of the above gives you heartburn and makes you angry, then perhaps you aren't ready to become a photography business, and you need to rethink your definition of success.

We don't after all, have to define your success by sales figures, number of publications, web site visitors or other such measures. But, if we do decide that this is the measure of our success, then we are not only going to have to accept the business method, we are going to have to worship it.

Saturday, February 24, 2007

Stitching Old Images

I shot this several years ago and have shown a single image in colour for some time - it generates lots of comments but no sales. Tonight I was going through the files in Bridge and noticed that I had shot two images hand held with a 17-40 @ 17 mm. on my 10D, simply swinging the camera a little between images. I can't remember if I ever tried stitching the pair (they were meant for stitching) or not but anyway tonight I did - no problems using PTGui - good result. I liked the result in colour but felt it was a bit gaudy so converted it to black and white and made some further contrast and local adjustments and I like this result.

The image was shot at the top of a ladder looking into a huge old water tank - about 40 feet across and 20 feet deep, the sides rusted and the bottom with about a foot of water and assorted growth. Beams across the top of the tank gave the odd radial shadows on the water. It was shot at noon so most of the tank is lit (I live in Calgary, so the sun is never right overhead).

It does bring up the point that if you don't do the stitching you planned, you may miss out on some good images. With stitching more automatic these days (no need to select dozens of control points manually any more), there's not a lot of excuse for not checking out the results of any stitches you intended.

Dealing With Disappointment

I found out yesterday I wasn't one of the selected photographers to attend Review Santa Fe. Today I went down to the Glenbow Museum (which has sold some of my images in their gift shop) to see what needed replacing, and they don't want any more images at the moment. I drove around this afternoon looking for something interesting to photograph (railway yards, industrial side of town, etc.) and didn't find anything.

Rejection is reality. The odds of being successful with every endevour is extremely unlikely and besides, if you only did things which were guaranteed to be successful, then you aren't pushing yourself very hard.

My options to deal with this ego insult include:

- sulking - I'm quite good at that

- getting depressed - I'm a lousy photographer with an over inflated self worth and it was time reality sunk in - my photography sucks - I should give up pretending to be any good... I'm quite good at this too.

- getting mad - those damn so and so's wouldn't recognize a good photograph if it slapped them in the face...

- getting even - I'll write those so and sos and give them a piece of my mind (not that I can afford to give any away)...

- worrying - what if all my attempts fail..., how will I cope, what if I've run out of original ideas, etc....

- give up - I've done this in the past - one time I gave up photography for 15 years - dumn idea!

- pick your own dysfunctional response

- cry on someone's shoulder - not bad, I can recommend this one

- pretend it didn't happen - that's a tough one - I'm not very good at that

- put it behind me and move on - perhaps submitting elsewhere (though it would be a pity not to learn from this experience).

- use cognitive therapy techniques to analyse faulty thinking and look at what was really being said here - this is definitely on the right track - and I'll explain more

I'm sure you can come up with some other responses, some of them likely others useful (usually not both).

In my role as a physician doing a fair amount of work in mental health, I had to learn about counselling and in particular about cognitive therapy - a form of counselling that has some scientific backing and track record to it.

One part of cognitive therapy is teaching patients to analyse their thoughts for cognitive or thinking errors. These take a number of forms and this isn't a course in cognitive therapy, but some of the errors in thinking apply to photographers dealing with rejection. it teaches you to analyse what was actually said, not what you inferred.

I have been rejected by this one person or group - therefore I'm going to be rejected by everybody - that's called generalization

This person doesn't like my photographs enough to select them for publication or whatever, therefore all my photographs suck - black and white thinking.

So, having got past the inital disappointment, I reread the email and in fact it included a fair amount of description of why the majority of the 592 photographers were rejected - either their portfolio wasn't a single project, or done with a single technique, or the style of photography was derivative.

Well, after calming down I remember that while all the images I submitted were industrial, some were close ups, others much further back, some were new new and shiny objects, others were rusted and old, images varied from container ships to old mine equipment.

It may be true that the images weren't good but my portfolio was not well defined and could easily have been rejected for that reason alone. I have no right to assume the work had no merit.

they said some photographers work was deriviative - well frankly I think all photographs are derivative - it's nigh on impossible to create new interesting work without a working knowledge of what has gone before. Of course, they may have meant that they were looking for odd, funky and really different images, which mine certainly weren't. I refuse to appologise for that - it's the kind of work I do and wouldn't change that if I could.

People often compare my work to that of Edward Burtynsky, another much more successful, well known and talented photorapher also from Canada and also photographing industrial subjects. I don't happen to think his images look anything like mine. His epmphasize destruction of landscape by industry and have more political overtones (I'd be more popular with galleriesif I followed suit but it isn't what i want to do). His images generally step back and include the surroundings - mine move in and are more abstract and I think creative (or at least created) images.

When rejected, it's important to put the rejection into perspective. Is there evidence that your photography is in fact worth while. Who has in fact mde nice comments about your work, who asked for a print, which publications accepted your work, etc.

Before ever getting published, this can be a tough one, but perhaps your work was admired or even given prizes at the local camera club. Maybe you were able to persuade a local bistro to hang some of your work, hey, at least your mother says she likes your photographs!

In the end, you have to ask yourself, did I set out on this adventure called photography so I could become famous, or so I could express myself, or so I could make money.

If the latter, then baby photographs, pets and weddings are probably the right direction to make the big bucks, if your goal is to become famous, then you have chosen a hard way to do it, bank robbery might be a better alternative (see getting rich), if you photograph to express yourself (and it's ok to like people saying nice things about your work), then does it really matter in the long run that one person or group didn't need your photographs that you submited, at this time?

Hell, I just want to go photographing.

Rejection is reality. The odds of being successful with every endevour is extremely unlikely and besides, if you only did things which were guaranteed to be successful, then you aren't pushing yourself very hard.

My options to deal with this ego insult include:

- sulking - I'm quite good at that

- getting depressed - I'm a lousy photographer with an over inflated self worth and it was time reality sunk in - my photography sucks - I should give up pretending to be any good... I'm quite good at this too.

- getting mad - those damn so and so's wouldn't recognize a good photograph if it slapped them in the face...

- getting even - I'll write those so and sos and give them a piece of my mind (not that I can afford to give any away)...

- worrying - what if all my attempts fail..., how will I cope, what if I've run out of original ideas, etc....

- give up - I've done this in the past - one time I gave up photography for 15 years - dumn idea!

- pick your own dysfunctional response

- cry on someone's shoulder - not bad, I can recommend this one

- pretend it didn't happen - that's a tough one - I'm not very good at that

- put it behind me and move on - perhaps submitting elsewhere (though it would be a pity not to learn from this experience).

- use cognitive therapy techniques to analyse faulty thinking and look at what was really being said here - this is definitely on the right track - and I'll explain more

I'm sure you can come up with some other responses, some of them likely others useful (usually not both).

In my role as a physician doing a fair amount of work in mental health, I had to learn about counselling and in particular about cognitive therapy - a form of counselling that has some scientific backing and track record to it.

One part of cognitive therapy is teaching patients to analyse their thoughts for cognitive or thinking errors. These take a number of forms and this isn't a course in cognitive therapy, but some of the errors in thinking apply to photographers dealing with rejection. it teaches you to analyse what was actually said, not what you inferred.

I have been rejected by this one person or group - therefore I'm going to be rejected by everybody - that's called generalization

This person doesn't like my photographs enough to select them for publication or whatever, therefore all my photographs suck - black and white thinking.

So, having got past the inital disappointment, I reread the email and in fact it included a fair amount of description of why the majority of the 592 photographers were rejected - either their portfolio wasn't a single project, or done with a single technique, or the style of photography was derivative.

Well, after calming down I remember that while all the images I submitted were industrial, some were close ups, others much further back, some were new new and shiny objects, others were rusted and old, images varied from container ships to old mine equipment.

It may be true that the images weren't good but my portfolio was not well defined and could easily have been rejected for that reason alone. I have no right to assume the work had no merit.

they said some photographers work was deriviative - well frankly I think all photographs are derivative - it's nigh on impossible to create new interesting work without a working knowledge of what has gone before. Of course, they may have meant that they were looking for odd, funky and really different images, which mine certainly weren't. I refuse to appologise for that - it's the kind of work I do and wouldn't change that if I could.

People often compare my work to that of Edward Burtynsky, another much more successful, well known and talented photorapher also from Canada and also photographing industrial subjects. I don't happen to think his images look anything like mine. His epmphasize destruction of landscape by industry and have more political overtones (I'd be more popular with galleriesif I followed suit but it isn't what i want to do). His images generally step back and include the surroundings - mine move in and are more abstract and I think creative (or at least created) images.

When rejected, it's important to put the rejection into perspective. Is there evidence that your photography is in fact worth while. Who has in fact mde nice comments about your work, who asked for a print, which publications accepted your work, etc.

Before ever getting published, this can be a tough one, but perhaps your work was admired or even given prizes at the local camera club. Maybe you were able to persuade a local bistro to hang some of your work, hey, at least your mother says she likes your photographs!

In the end, you have to ask yourself, did I set out on this adventure called photography so I could become famous, or so I could express myself, or so I could make money.

If the latter, then baby photographs, pets and weddings are probably the right direction to make the big bucks, if your goal is to become famous, then you have chosen a hard way to do it, bank robbery might be a better alternative (see getting rich), if you photograph to express yourself (and it's ok to like people saying nice things about your work), then does it really matter in the long run that one person or group didn't need your photographs that you submited, at this time?

Hell, I just want to go photographing.

Friday, February 23, 2007

Papers For Fine Art Prints

Some time ago I bought a Canon iPF 5000 specifically so that I could take advantage of the much touted new papers which purported to do a good job imitating traditional glossy dried matte photographic paper, long the standard fine art surface of most photographers.

it should be understood that while this surface was 'the standard', it doesn't necessarily mean it was or should be the gold standard by which everything else should be compared.

Truth is that matte silver papers are incapable of producing a decent black and have generally been shunned. The surface was very visible in dark areas. The same is NOT true of matte inkjet papers which both show a fairly decent black (OK, not tested nearly as dark as glossy papers and glossy inks, but pretty darn good none the less) and a surface which shows no reflections at all and so is essentially invisible. This is a huge improvement over silver matte papers and has made them the new 'standard' for fine art work. The lack of surface awareness makes them better in some ways than even traditional glossy dried matte which still has some reflection issues.

Now however, the issue is one of comparing the new inkjet 'glossy dried matte' papers. Specifically I'm talking about Crane Museo Silver Rag, Hahnemuhle Pearl and Innova Fibaprint F Gloss. I have now had a chance to try all three papers and here's my observations about these papers in general then specific comments about each paper.

All three papers have a slight sheen to the unprinted surface however this isn't nearly as shiny as the black ink so the result is that at angles, the ink really does look like it's sitting on top of the paper and the light areas are noticeably duller than the dark areas. This is the reverse of bronzing in which flat inks sat on top of glossy paper. I don't see why we couldn't have a slightly glossier paper which matches the gloss of the inks.

The blacks are good and yes, holding a print in hand, they do look deeper than matte prints though oddly it's more to do with picking up surface reflections than actually looking blacker. Under 150 watt spot lights I dare say the difference would be a lot more noticeable but that's not the real world of print viewing, in home or in galleries.

Silver Rag - was the first of the new papers. The paper is noticeably cream coloured especially when compared to the others. Some yellowing of lighter inks can be avoided by using a neutral ink setting rather than warm. The surface has a fair amount of texture - the most of the three papers. It has a natural look to it and is quite nice. If an image suits a warm paper, prints look very nice. Two boxes of paper had to be rejected due to surface defects that showed both before and after printing and every other box has shown some suface markings, all be it barely noticeable once printed on. A few sheets show scuffing of the surface as if the sheets have been rubbing on each other in the box - these have had to be relegated to test prints since it does show in the final print and these sheets can't be used for good prints. Given the cost per sheet, this is pretty significant. Silver rag has been the only paper which has not had bashed corners in some boxes - whether this is coincidence or better packing I'm not sure yet.

Pearl - two boxes showed bashed corners - fortunately a third box opened at the store also showed the same bashes showing it wasn't my fault. I don't remember anything like the same problems with silver gelatin photographic papers - was it the light tight wrapping or stiffness of the sheets - I don't know but I do know I'm frustrated and I'm at the point now that I will have to open every single box of paper in store before going home. I didn't have this problem to nearly the same extent with Moab Entrada for whatever reason. Pearl has a slightly finer surface than Silver Rag on a white paper. The texture is just a little bit repetitive (like a weave)in places but this is subtle and for the most part not an issue. Sheets show no defects at all, through the whole box. Review articles have suggested a deeper black than Silver Rag but I haven't seen the difference and if I can't see it I have no interest in measuring it. If you can live with the gloss differential and like a slight texture to the paper, this is a nice paper to work with.

Fibaprint F Gloss - I can't buy this paper locally but ordered some and waited a month for it to come. The texture is the least of the three and I chose this paper for submitting for magazine publication (though I suspect that if they accept the images, they will probably want the digital files anyway). This isn't an all rag art paper but lets face it, silver gelatin paper was never all rag either. It is however lignin free and should be archival. The surface has been free of defects. I don't happen to like their plastic boxes for the paper but that wouldn't prevent me from using the paper. If you want as little suface texture and as close as possible to glossy dried matte, then this is probably the paper you should use.

After all this discussion of the new papers, I'm still not sure that I'm not going to go back to using matte for most of my work. As I've written in the past, once matte papers are behind glass, there is no noticeable diffecence between them and glossier papers, except for reduced reflections with the matte paper, and without the gloss differential as discussed above.

it should be understood that while this surface was 'the standard', it doesn't necessarily mean it was or should be the gold standard by which everything else should be compared.

Truth is that matte silver papers are incapable of producing a decent black and have generally been shunned. The surface was very visible in dark areas. The same is NOT true of matte inkjet papers which both show a fairly decent black (OK, not tested nearly as dark as glossy papers and glossy inks, but pretty darn good none the less) and a surface which shows no reflections at all and so is essentially invisible. This is a huge improvement over silver matte papers and has made them the new 'standard' for fine art work. The lack of surface awareness makes them better in some ways than even traditional glossy dried matte which still has some reflection issues.

Now however, the issue is one of comparing the new inkjet 'glossy dried matte' papers. Specifically I'm talking about Crane Museo Silver Rag, Hahnemuhle Pearl and Innova Fibaprint F Gloss. I have now had a chance to try all three papers and here's my observations about these papers in general then specific comments about each paper.

All three papers have a slight sheen to the unprinted surface however this isn't nearly as shiny as the black ink so the result is that at angles, the ink really does look like it's sitting on top of the paper and the light areas are noticeably duller than the dark areas. This is the reverse of bronzing in which flat inks sat on top of glossy paper. I don't see why we couldn't have a slightly glossier paper which matches the gloss of the inks.

The blacks are good and yes, holding a print in hand, they do look deeper than matte prints though oddly it's more to do with picking up surface reflections than actually looking blacker. Under 150 watt spot lights I dare say the difference would be a lot more noticeable but that's not the real world of print viewing, in home or in galleries.

Silver Rag - was the first of the new papers. The paper is noticeably cream coloured especially when compared to the others. Some yellowing of lighter inks can be avoided by using a neutral ink setting rather than warm. The surface has a fair amount of texture - the most of the three papers. It has a natural look to it and is quite nice. If an image suits a warm paper, prints look very nice. Two boxes of paper had to be rejected due to surface defects that showed both before and after printing and every other box has shown some suface markings, all be it barely noticeable once printed on. A few sheets show scuffing of the surface as if the sheets have been rubbing on each other in the box - these have had to be relegated to test prints since it does show in the final print and these sheets can't be used for good prints. Given the cost per sheet, this is pretty significant. Silver rag has been the only paper which has not had bashed corners in some boxes - whether this is coincidence or better packing I'm not sure yet.

Pearl - two boxes showed bashed corners - fortunately a third box opened at the store also showed the same bashes showing it wasn't my fault. I don't remember anything like the same problems with silver gelatin photographic papers - was it the light tight wrapping or stiffness of the sheets - I don't know but I do know I'm frustrated and I'm at the point now that I will have to open every single box of paper in store before going home. I didn't have this problem to nearly the same extent with Moab Entrada for whatever reason. Pearl has a slightly finer surface than Silver Rag on a white paper. The texture is just a little bit repetitive (like a weave)in places but this is subtle and for the most part not an issue. Sheets show no defects at all, through the whole box. Review articles have suggested a deeper black than Silver Rag but I haven't seen the difference and if I can't see it I have no interest in measuring it. If you can live with the gloss differential and like a slight texture to the paper, this is a nice paper to work with.

Fibaprint F Gloss - I can't buy this paper locally but ordered some and waited a month for it to come. The texture is the least of the three and I chose this paper for submitting for magazine publication (though I suspect that if they accept the images, they will probably want the digital files anyway). This isn't an all rag art paper but lets face it, silver gelatin paper was never all rag either. It is however lignin free and should be archival. The surface has been free of defects. I don't happen to like their plastic boxes for the paper but that wouldn't prevent me from using the paper. If you want as little suface texture and as close as possible to glossy dried matte, then this is probably the paper you should use.

After all this discussion of the new papers, I'm still not sure that I'm not going to go back to using matte for most of my work. As I've written in the past, once matte papers are behind glass, there is no noticeable diffecence between them and glossier papers, except for reduced reflections with the matte paper, and without the gloss differential as discussed above.

Papers For Fine Art Prints

Some time ago I bought a Canon iPF 5000 specifically so that I could take advantage of the much touted new papers which purported to do a good job imitating traditional glossy dried matte photographic paper, long the standard fine art surface of most photographers.

it should be understood that while this surface was 'the standard', it doesn't necessarily mean it was or should be the gold standard by which everything else should be compared.

Truth is that matte silver papers are incapable of producing a decent black and have generally been shunned. The surface was very visible in dark areas. The same is NOT true of matte inkjet papers which both show a fairly decent black (OK, not tested nearly as dark as glossy papers and glossy inks, but pretty darn good none the less) and a surface which shows no reflections at all and so is essentially invisible. This is a huge improvement over silver matte papers and has made them the new 'standard' for fine art work. The lack of surface awareness makes them better in some ways than even traditional glossy dried matte which still has some reflection issues.

Now however, the issue is one of comparing the new inkjet 'glossy dried matte' papers. Specifically I'm talking about Crane Museo Silver Rag, Hahnemuhle Pearl and Innova Fibaprint F Gloss. I have now had a chance to try all three papers and here's my observations about these papers in general then specific comments about each paper.

All three papers have a slight sheen to the unprinted surface however this isn't nearly as shiny as the black ink so the result is that at angles, the ink really does look like it's sitting on top of the paper and the light areas are noticeably duller than the dark areas. This is the reverse of bronzing in which flat inks sat on top of glossy paper. I don't see why we couldn't have a slightly glossier paper which matches the gloss of the inks.

The blacks are good and yes, holding a print in hand, they do look deeper than matte prints though oddly it's more to do with picking up surface reflections than actually looking blacker. Under 150 watt spot lights I dare say the difference would be a lot more noticeable but that's not the real world of print viewing, in home or in galleries.

Silver Rag - was the first of the new papers. The paper is noticeably cream coloured especially when compared to the others.

it should be understood that while this surface was 'the standard', it doesn't necessarily mean it was or should be the gold standard by which everything else should be compared.

Truth is that matte silver papers are incapable of producing a decent black and have generally been shunned. The surface was very visible in dark areas. The same is NOT true of matte inkjet papers which both show a fairly decent black (OK, not tested nearly as dark as glossy papers and glossy inks, but pretty darn good none the less) and a surface which shows no reflections at all and so is essentially invisible. This is a huge improvement over silver matte papers and has made them the new 'standard' for fine art work. The lack of surface awareness makes them better in some ways than even traditional glossy dried matte which still has some reflection issues.

Now however, the issue is one of comparing the new inkjet 'glossy dried matte' papers. Specifically I'm talking about Crane Museo Silver Rag, Hahnemuhle Pearl and Innova Fibaprint F Gloss. I have now had a chance to try all three papers and here's my observations about these papers in general then specific comments about each paper.

All three papers have a slight sheen to the unprinted surface however this isn't nearly as shiny as the black ink so the result is that at angles, the ink really does look like it's sitting on top of the paper and the light areas are noticeably duller than the dark areas. This is the reverse of bronzing in which flat inks sat on top of glossy paper. I don't see why we couldn't have a slightly glossier paper which matches the gloss of the inks.

The blacks are good and yes, holding a print in hand, they do look deeper than matte prints though oddly it's more to do with picking up surface reflections than actually looking blacker. Under 150 watt spot lights I dare say the difference would be a lot more noticeable but that's not the real world of print viewing, in home or in galleries.

Silver Rag - was the first of the new papers. The paper is noticeably cream coloured especially when compared to the others.

Wednesday, February 21, 2007

Carreer, Family And Photography

I suspect I am in a situation familiar to any number of you. I treat my photography seriously, I'd like others to treat my photography seriouisly, yet at the same time, I have a carreer and family and have to make compromises.

Some choose to risk abandoning security and becoming full time professional photographers. A small minority are successful while many are forced to give up, with their finances ruined and lives stressed beyond reason. Those who make the transition successfully are by and large anything but fine art photographers. Those who say they are full time fine art photographers in fact spend 90 percent of their time doing sales, paper work, accounting, advertizing and just about anything but photography. Even people like Bruce Barnbaum teach workshops and take private students and write articles to support themselves.

I don't have any brilliant solutions to this problem but here's a few thoughts to ponder.

Your long term goals may be impractical but it's possible to set some short term goals which will help those long term ones. For example, you may not be in a position to have a one man show of 50 images, but you could certainly be working on some long term projects so that 10 years from now, when you have the time, money and reputation, you will have enough images with a theme to put together a cohesive show.

Some goals are more practical than others. A porfolio of 12 good images might be doable while 50 isn't. A set of beautiful 8X10 images may be affordable where a set of 16X20's or larger isn't.

It would be nice to have an entire article to yourself, but how about starting with some images in the readers section of your favourite magazine.

MOMA may be out of reach for now, but a local restaurant might want your images. It may well be that you can only get out on a serious shoot a handful of times a year at best, but you can keep working on your skills with small local projects - still lifes, urban, street photography etc.

Having a different job really gets in the way of being taken seriously. When you should be going round the galleries to promote your work to curators, you are at work instead. When you should be out shooting and creating more images, you are taking the kids to hockey, or making those prints for the restaurant.

The only cosolation I can offer you is that you are in good company, many of us struggle with the same issues. Progress to goals can be made, just not as fast as if you had all your time to devote to photography.

Keep in mind that it's your regular job which has allowed you to purchase your nice camera equipment.

Some choose to risk abandoning security and becoming full time professional photographers. A small minority are successful while many are forced to give up, with their finances ruined and lives stressed beyond reason. Those who make the transition successfully are by and large anything but fine art photographers. Those who say they are full time fine art photographers in fact spend 90 percent of their time doing sales, paper work, accounting, advertizing and just about anything but photography. Even people like Bruce Barnbaum teach workshops and take private students and write articles to support themselves.

I don't have any brilliant solutions to this problem but here's a few thoughts to ponder.

Your long term goals may be impractical but it's possible to set some short term goals which will help those long term ones. For example, you may not be in a position to have a one man show of 50 images, but you could certainly be working on some long term projects so that 10 years from now, when you have the time, money and reputation, you will have enough images with a theme to put together a cohesive show.

Some goals are more practical than others. A porfolio of 12 good images might be doable while 50 isn't. A set of beautiful 8X10 images may be affordable where a set of 16X20's or larger isn't.

It would be nice to have an entire article to yourself, but how about starting with some images in the readers section of your favourite magazine.

MOMA may be out of reach for now, but a local restaurant might want your images. It may well be that you can only get out on a serious shoot a handful of times a year at best, but you can keep working on your skills with small local projects - still lifes, urban, street photography etc.

Having a different job really gets in the way of being taken seriously. When you should be going round the galleries to promote your work to curators, you are at work instead. When you should be out shooting and creating more images, you are taking the kids to hockey, or making those prints for the restaurant.

The only cosolation I can offer you is that you are in good company, many of us struggle with the same issues. Progress to goals can be made, just not as fast as if you had all your time to devote to photography.

Keep in mind that it's your regular job which has allowed you to purchase your nice camera equipment.

Tuesday, February 20, 2007

Exercise In Angles

Sunday, February 18, 2007

Subtle Isn't Synonomous With Weak

If an image is not dramatic, it's very tempting to file it away as weak. If someone says your image is subtle, it's all too easy to equate that with 'nice try', with the emphasis on 'try'.

So: it seems to me we need to define subtle as it relates to images. A subtle hint is one which you might well miss if not paying attention. Subtle music takes careful and repeated listening to get it. A subtle outfit is one which doesn't draw attention to itself yet all the pieces, ordinary in themselves, somehow come together in harmony.

Here's what Wiki has as a definition of subtle:

sub·tle (stl)

adj. sub·tler, sub·tlest

1.

a. So slight as to be difficult to detect or describe; elusive: a subtle smile.

b. Difficult to understand; abstruse: an argument whose subtle point was lost on her opponent.

2. Able to make fine distinctions: a subtle mind.

3.

a. Characterized by skill or ingenuity; clever.

b. Crafty or sly; devious.

c. Operating in a hidden, usually injurious way; insidious: a subtle poison.

I think we can now say some things about a subtle photograph.

a) not everyone is going to 'get' it

b) even those who do, are probably going to have to work at it - no freebees here

c) it's likely to take time - you are going to have to live with the image - for minutes, hours, possibly even years

d) it's meaning is probably hidden in complexity

e) there's a good chance the image works in a number of different ways - ie. the more you study it, the more you 'get'

f) subtle doesn't necessarily mean peaceful - a subtle image can make you very uncomfortable in time - it just doesn't slap you on the face

g) subtle images are going to be damn hard to make and it would be very easy to kid ourselves that a weak image is a subtle one.

h) this makes life really complicated - what if it isn't subtle, what if it truly is just as bad as you first thought?

i) it's possible for an image to be both subtle and dramatic - the former hidden under the latter.

Think of it as being like playing chess. To be successful, it's necessary to plan several moves ahead - I'd like to do this but I have to watch out for that, and I have to block the other...

I'd like to think that the images which I strongly like and which receive very little acclaim, do so because they are subtle. Of course, there's no real way to know for sure - I guess I have to wait till after I'm dead to find out - and even then, if I'm lucky enough to be remembered for images, it isn't likely to be the subtle ones anyway.

If anyone has a sure fire way to identify subtle images from 'nice try's' please 'to tell us' how.

Does An Image Need A Centre Of Interest?

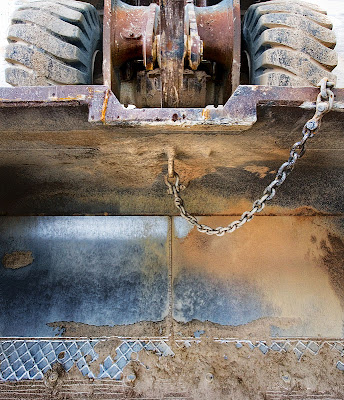

It's generally assumed that a photograph should have a centre of interest (or possibly more than one). Does this mean that an image which has no particular areas of strong attention can't make a good photograph? What if it is the whole image that is important rather than particular parts of it? The image above has no centre of interest but I like it anyway. No one part of it jumps out at you yet removing any of the parts would weaken the image.

So, I think the answer is that yes, a centre of interest is not necessary.

Friday, February 16, 2007

It Takes Time

The image above is from our holiday last Fall. It's not that I haven't looked at this image before, it just never quite caught my attention. It seemed cluttered and the colour didn't quite work - green water to the left and an odd green tinge to some of the rocks, but not a complementary green...

Last night I decided to work with the image as far as I could take it in colour, but with the idea that I'd almost certainly switch to black and white - can't really tell you why I didn't just go to black and white first, it makes more sense, but I guess I wanted to see if the colour could be made to work - it couldn't.

In black and white and much darker than as shot, I quite like it and feel that the clutter is starting to hang together, enough to make the photograph interesting rather than cluttered (my opinion, obviously). Haven't printed it yet, but think that I might just be able to get some lovely tones out of those rocks part in shade.

Thursday, February 15, 2007

Autofocus?

I remember the days when we scoffed at the idea of auto focus - how could a machine possibly focus more accurately than the human eye, etc., etc.. Well, we've had to retract those ideas a long time since but it doesn't hurt to discuss the uses of auto focus. In my 1Ds2 auto focus is more accurate than my focusing, it's also a hell of a lot faster. I can't comment on it's follow focus abilities since I don't tend to do that kind of work but understand that it's pretty good.

That being the case, how come most of my lenses spend most of their time on manual focus, and does that mean the auto focus feature is a waste of time?

The problem for me with auto focus is I don't know for sure where it's focusing - sure I know which little focus rectangle lit up, but was it focusing on the branch in front or the one in back. My preferred use of auto focus is focus confirmation - ie. I turn off auto-focus on the lens, focus manually and usually but not always use the focus confirmation feature (in my camera the focus rectangle lights up) to confirm that I got the focus right. I may well move the camera so that it's clear what I'm focusing on. Occasionally I will use auto-focus when I can't see well enough - this is particularly true of wide angle f4 lenses. Sometimes I will auto focus, switch to manual move the camera and then take the picture (the half press of the shutter idea not working when I use a cable release).

Where I am relying on depth of field to cover a near far situation, the traditional rule of thumb is to focus 1/3 of the way from near to far to split the depth of field equally. As this happens to correspond to the centre of the image, if the near and far limits are equidistant from the edges of the image, then I just frame and focus. If not, then I aim for focus, switch to manual, and move the camera to the final framing.

That being the case, how come most of my lenses spend most of their time on manual focus, and does that mean the auto focus feature is a waste of time?

The problem for me with auto focus is I don't know for sure where it's focusing - sure I know which little focus rectangle lit up, but was it focusing on the branch in front or the one in back. My preferred use of auto focus is focus confirmation - ie. I turn off auto-focus on the lens, focus manually and usually but not always use the focus confirmation feature (in my camera the focus rectangle lights up) to confirm that I got the focus right. I may well move the camera so that it's clear what I'm focusing on. Occasionally I will use auto-focus when I can't see well enough - this is particularly true of wide angle f4 lenses. Sometimes I will auto focus, switch to manual move the camera and then take the picture (the half press of the shutter idea not working when I use a cable release).

Where I am relying on depth of field to cover a near far situation, the traditional rule of thumb is to focus 1/3 of the way from near to far to split the depth of field equally. As this happens to correspond to the centre of the image, if the near and far limits are equidistant from the edges of the image, then I just frame and focus. If not, then I aim for focus, switch to manual, and move the camera to the final framing.

How Long And Narrow Can A Print Be?

Panoramic images are getting quite popular. The Linhof and Fuji 6X17 cameras, banquet large format cameras of 5X12, 7X17 and 8X20 are seeing a return to favour, and those of us stitching digital images can make images of any ratio we care to.

So, if long and narrow is good (and I think it's easy to prove that it can be), just how wide and narrow can one go? You could simply go with what you like, but that avoids the question of whether your viewers are likely to appreciate what you're doing.

During my two years selling prints at the local farmers market I was surprised at how popular panoramic images were. My Columbia Ice Fields image which is an 8 image stitch is particularly popular and the bottom line is people often ask for panoramas to decorate long walls - they'd rather have a single large image over the bed or the sofa than say a series of three. On a practical level, 4:1 is about as long as works in decorating and 3:1 is more popular.

I'd leave longer pans for special circumstances.

Tuesday, February 13, 2007

Jura Canyon Blend

The image above is made up of a total of 20 images. The left hand wall required 11 images blended in Helicon Focus to cope with the huge depth of field requirement while other parts of the image took fewer. The image is stitched from the output of 5 different blends. The images didn't line up properly in photoshop but were close enough that with adjusting the seams between images, the flaws were hidden. This would not have been possible had this been a less homogenious subject. It might have been possible to use PTGui or even to resize the individual images to better blend them, but it worked this way.

Grump About Camera Bags

When I shot 4X5 I had an ideal camera bag - it cost about $30, held my lenses underneath my camera, was backpackable but stood upright without risk of falling over, hell it even had wheels to roll it if I wanted. It had a pocket for 12 holders of unexposed, likewise for exposed and sev. other pockets for filters, cables, cleaning equipment etc. it was purchased in a discount luggage store. It was so good I bought a second one to replace the first when it wore out - one zip has gone a bit iffy but otherwise it's fine. I had to modify it by putting feet on it (wooden, screwed into roller support and that's what made it stable even on a 30 degree slope.

Now I'm shooting with a DSLR and so I followed the crowd and purchased a Lowepro bag. It gets dirty every time I put it down, and the bit that gets dirty is the part that then rubs up against me - ie. the back and the straps. It can't reliably sit upright. It can't be picked up safely without zipping it up all the way - I lost a lens learning that one. When my very heavy 1Ds2 sits on the top of the bag, it worms it's way downwards because the foam and velcro holders only work when the bag is completely full of equipment. That means you can't leave enough space for a long lens on the body. Larger lenses like my 24-70 are too fat to fit the length of dividers supplied and getting stuff out of the bottom involves undoing two zips and laying out the case, now getting another surface wet or dirty or both.

At 25+ lb. only a backpack makes sense but does anyone else have the same complaints, or more importantly does anyone have a solution?

Now I'm shooting with a DSLR and so I followed the crowd and purchased a Lowepro bag. It gets dirty every time I put it down, and the bit that gets dirty is the part that then rubs up against me - ie. the back and the straps. It can't reliably sit upright. It can't be picked up safely without zipping it up all the way - I lost a lens learning that one. When my very heavy 1Ds2 sits on the top of the bag, it worms it's way downwards because the foam and velcro holders only work when the bag is completely full of equipment. That means you can't leave enough space for a long lens on the body. Larger lenses like my 24-70 are too fat to fit the length of dividers supplied and getting stuff out of the bottom involves undoing two zips and laying out the case, now getting another surface wet or dirty or both.

At 25+ lb. only a backpack makes sense but does anyone else have the same complaints, or more importantly does anyone have a solution?

Monday, February 12, 2007

The Edges Of An Image

Traditional (and even some current) photography books recommend using the edges of the image to frame the picture. They suggest overhanging branches or trees on either side.

In general, I hate overhanging branches used as a frame, particularly when they don't have a trunk in the image from which to sprout.

But that leaves us with the question of what good are the edges of the image. Do they only serve to give the subject some space, or to keep your eye from wandering off to the right and out of the picture (another traditional piece of advice)?

What if instead we considered the edges of the image - that last inch or so of the print as being every bit as important as the centre of interest (which usually but not always is away from the centre)?

Strong composition demands good use of all the real estate of the image.

Let's take the example of a long lens image of a rugby tackle - with a long lens, only the ball and the fingers of the tackler digging into the thigh of the runner with the ball are sharp, the background completely blurred.

The lines that show, all be it blurred, are part of the composition and either form interesting shapes or help emphasize the ball and the hand, or they don't. If the left edge of the image is sharp while the right is blurred, there is a sense of imbalance, not to say distraction. The blurred background could be grass or the rest of the team roaring up, but ideally it contributes to the picture. Odds are that if the tackle happened on the side lines right in front of the photographer who happened to have a 28 mm. lens on one body, the photograph wouldn't be as powerful as if shot in the distance with the isolating power of the long lens.

Lines can run parallel to the edge of the image, resulting in stability, or they can angle ever so slightly and introduce tension. Lines can cross the edge or radiate from a corner. Shapes which can be real or simply of similar tones, or they can be shadows, or just large blurred areas. the edge of the shadow can just reach the edge of the print, or almost reach it or go a bit past it or can appear to be still expanding at the edge of the print - each gives a different feeling.

An edge can give the feeling that something is continuing, or it can give you the sense that you are missing something important beyond the edge - the latter being generally undesireable. A shape that is still expanding implies there may be more, one that is already contracting at the edge isn't likely to give that feeling.

Don't forget the space between shapes - that too is a shape and can be important.

The edges of the image can be light or dark but take into consideration the viewing circumstances - if the image has to be mounted on white board - say for an upcoming show - a lot of white at the edges can be a problem. Consider changing the background colours on screen in Photoshop to test various situations. Try printing the image with a large white border and see how it looks.

Fred Picker used to recommend burning in the eges of the print as a matter of routine. While some of this had to do with light falloff in the enlarger, he was also aware that strengthening the edges helped focus the eyes within the image. An area which you might want just barely off white in the middle of the image, may be better burned down a bit at the edges even if it's the same subjet material (though remember to be subtle here).

Bottom line is make your edges earn their keep.

In general, I hate overhanging branches used as a frame, particularly when they don't have a trunk in the image from which to sprout.

But that leaves us with the question of what good are the edges of the image. Do they only serve to give the subject some space, or to keep your eye from wandering off to the right and out of the picture (another traditional piece of advice)?

What if instead we considered the edges of the image - that last inch or so of the print as being every bit as important as the centre of interest (which usually but not always is away from the centre)?

Strong composition demands good use of all the real estate of the image.

Let's take the example of a long lens image of a rugby tackle - with a long lens, only the ball and the fingers of the tackler digging into the thigh of the runner with the ball are sharp, the background completely blurred.

The lines that show, all be it blurred, are part of the composition and either form interesting shapes or help emphasize the ball and the hand, or they don't. If the left edge of the image is sharp while the right is blurred, there is a sense of imbalance, not to say distraction. The blurred background could be grass or the rest of the team roaring up, but ideally it contributes to the picture. Odds are that if the tackle happened on the side lines right in front of the photographer who happened to have a 28 mm. lens on one body, the photograph wouldn't be as powerful as if shot in the distance with the isolating power of the long lens.

Lines can run parallel to the edge of the image, resulting in stability, or they can angle ever so slightly and introduce tension. Lines can cross the edge or radiate from a corner. Shapes which can be real or simply of similar tones, or they can be shadows, or just large blurred areas. the edge of the shadow can just reach the edge of the print, or almost reach it or go a bit past it or can appear to be still expanding at the edge of the print - each gives a different feeling.

An edge can give the feeling that something is continuing, or it can give you the sense that you are missing something important beyond the edge - the latter being generally undesireable. A shape that is still expanding implies there may be more, one that is already contracting at the edge isn't likely to give that feeling.

Don't forget the space between shapes - that too is a shape and can be important.

The edges of the image can be light or dark but take into consideration the viewing circumstances - if the image has to be mounted on white board - say for an upcoming show - a lot of white at the edges can be a problem. Consider changing the background colours on screen in Photoshop to test various situations. Try printing the image with a large white border and see how it looks.

Fred Picker used to recommend burning in the eges of the print as a matter of routine. While some of this had to do with light falloff in the enlarger, he was also aware that strengthening the edges helped focus the eyes within the image. An area which you might want just barely off white in the middle of the image, may be better burned down a bit at the edges even if it's the same subjet material (though remember to be subtle here).

Bottom line is make your edges earn their keep.

Sunday, February 11, 2007

Wither Black and White Or Colour?

Chuck, in an attempt to distract me from photographing any more underwear, has asked about how I decide whether to make an image colour or black and white.

Sometimes subtle tonal gradations call out for black and white and quite early I'll convert the image and see how it works. Other times, the colours clearly don't work together and the only hope for the image is in black and white - whether I realized that at the time of shooting or not.

I have to say that I'm glad we don't have to choose at the time of shooting, more than once I have planned wrongly - subtle colours were worth preserving when I thought the image only suitable for black and white, or the reverse.

Sometimes I'm well into the process of editing the image before I decide I'd like to look at it in black and white.

So: here's the list of decisions

1) if the image is part of a series, then I continue with colour or black and white as was started.

2) if the subject matter (as opposed to the colours) strongly suggests one medium over the other, then...

3) Sometimes I know which i want when I aim the camera.

4) Often but not always I will try the image both ways and see which works better, and

5) Occasionally I can't make up my mind and I keep the image both ways.

Friday, February 09, 2007

Inferno

This is a different picture of the same trunk that supplied the black and white image of the other day. This too is a crop.

Another point to be considered in cropping is that with a 35 mm. slr view finder, exact cropping is difficult - even with a view finder as accurate as the one on the 1Ds2 - giving yourself just a little room will slightly reduce maximum print size, ever so slightly over cropping in camera can ruin a picture. Mind you, we're talking an extra 2% around the image just to be safe, not 30%.

Workflow

Chuck asked about my workflow, having commented on my 'wood abstract' image. For a detailed discussion I refer you to the four articles I wrote for Outback Photo.

More particularly, Chuck is right, this image was not only cropped, it was rotated 90 degrees which doesn't often happen. the sequence was:

- camera raw 1 size up output to photoshop - 16 bit of course

- tried various crops - the whole image was of a tree trunk and included air space on either side but I wanted to concentrate on the weathering patterns. I ended up with a tall skinny crop and thought it would look better on it's side, subject to odd shadows not being a problem - there weren't any

- some increase in contrast and darkening in the light area to the left

- cloning out a dark branch that cut across the lower left corner

- Akvis Enhancer (full strength for a change)

- smart sharpen

- general tonal adjustments

- conversion to black and white using Russell Brown technique of two hue adjustment layers, the lower one set to colour and the hue slider used to 'filter' the black and white image to taste

- further contrast and tonal adjustments both globally and locally once it was in black and white to suit.

I don't think this is a particularly strong image and I doubt I'll ever get round to printing it - I confess I was scrounging old files for something to show that hadn't been displayed before. That said, the workflow is fairly typical. I try to remember to smart sharpen first before doing the akvis enhancing - but I forgot in this case and it didn't seem to matter - sometimes the changes akvis creates to increase local contrast, when sharpened, go really wild but I got away with it in this image.

More particularly, Chuck is right, this image was not only cropped, it was rotated 90 degrees which doesn't often happen. the sequence was:

- camera raw 1 size up output to photoshop - 16 bit of course

- tried various crops - the whole image was of a tree trunk and included air space on either side but I wanted to concentrate on the weathering patterns. I ended up with a tall skinny crop and thought it would look better on it's side, subject to odd shadows not being a problem - there weren't any

- some increase in contrast and darkening in the light area to the left

- cloning out a dark branch that cut across the lower left corner

- Akvis Enhancer (full strength for a change)

- smart sharpen

- general tonal adjustments

- conversion to black and white using Russell Brown technique of two hue adjustment layers, the lower one set to colour and the hue slider used to 'filter' the black and white image to taste

- further contrast and tonal adjustments both globally and locally once it was in black and white to suit.

I don't think this is a particularly strong image and I doubt I'll ever get round to printing it - I confess I was scrounging old files for something to show that hadn't been displayed before. That said, the workflow is fairly typical. I try to remember to smart sharpen first before doing the akvis enhancing - but I forgot in this case and it didn't seem to matter - sometimes the changes akvis creates to increase local contrast, when sharpened, go really wild but I got away with it in this image.

Finding Inspiration