Doug in a comment on my last post refers to the often noted phenomenon of having personal favourites that other people just don't like.

It's almost like those tests for colour blindness where you look at the subtly coloured dots and try to see the number amongst the random variation - normal people can see the number clearly, colour blind people look at you like you're crazy - 'there's no number there'. Since this phenomenon works with black and white images, my analogy has severe limits, but it seems like that.

So what could be happening here, how is it that we see greatness in an image that no one else sees? Seems to me there area couple of possibilities.

1) there is a connection between you and the subject matter which doesn't show in the picture but which you of course remember so for you it's as if the picture did show this connection.

2) You can see patterns and relationships in the picture where other people just see clutter. I know I'm guilty of trying to justify a picture because of some tenuous at best patterns in the picture - the left bottom balances the top right, blah, blah, blah... only I'm really stretching it - in those situations, I usually stop kidding myself and abandon the image, and these are never the images I feel really strongly about anyway so perhaps that's not the answer. On the other hand, perhaps there are times that patterns jump out for us but don't show for others - perhaps because we remember the real scene, maybe because it relates to something in our lives - a favourite painting or even another photograph.

One can imagine that different people like different shapes and patterns but that would explain why only some people like a certain image but it doesn't explain why no one likes an image I feel strongly about. there aught to be some people who have similar tastes. No, it's more complicated than that.

Certainly, it's the more abstract images which are usually the ones which only the photographer likes - pictures of lighthouses are easy to sell. Some abstracts though are often admired even if not always purchased while others that are favourites get barely a glance.

Any further thoughts on what explains this phenomenon?

Wednesday, January 31, 2007

Tuesday, January 30, 2007

Why Are Some Of Our Images So Much Better?

Why is it that any one photographer may have hundreds of ordinary images but only a handful of really good ones? Is this the hallmark of an amateur or do all photographers have the same issues? Is it possible to change the ratio of really good images without improving all the images? Could it just be luck and 'time in the saddle', that essentially we have no control over this? These are important questions and the last one is downright scary - the idea that I have no control over now many good images I produce is discouraging, not to say depressing. But is it true?

I would argue that every photographer of whatever genre and style has the same problem - that a small percentage of his or her images are much stronger than all the others, that each of us has a 'portfolio' of images we want to be known by. The quality of those 'best' images varies from person to person, but the ratio doesn't. I suspect that all photographers have roughly the same percentage of images which stand out against the rest of their work.

Anything which would help you make more 'outstanding' images is likely to improve the worst of your images at least as much as the best of your photographs. The gap may change but it isn't ever going to go away.

I would further argue that we wouldn't want it to go away - we NEED those few really good images which show us we are capable of improving.

The same phenomenon of sometimes excelling is present in everything we do in life. Every so often a tennis player plays above himself and its the memory of that day which pushes him to keep trying, to practice more, to take lessons, buy a new racquet, do just about anything in fact to have that happen again. Of course when he improves, the bar is just raised that much higher.

Some days we are particularly attuned to the subject matter, we just seem to see more clearly, it's easier to put the many elements of a photograph together and it's easier to recognize potential subject matter. A different day and you'd walk right by.

Myriad factors play here - sleep, stress, fitness, mood. Some days those ground strokes work perfectly, other times the brain just doesn't talk to the hand - welcome to real life.

I would argue that every photographer of whatever genre and style has the same problem - that a small percentage of his or her images are much stronger than all the others, that each of us has a 'portfolio' of images we want to be known by. The quality of those 'best' images varies from person to person, but the ratio doesn't. I suspect that all photographers have roughly the same percentage of images which stand out against the rest of their work.

Anything which would help you make more 'outstanding' images is likely to improve the worst of your images at least as much as the best of your photographs. The gap may change but it isn't ever going to go away.

I would further argue that we wouldn't want it to go away - we NEED those few really good images which show us we are capable of improving.

The same phenomenon of sometimes excelling is present in everything we do in life. Every so often a tennis player plays above himself and its the memory of that day which pushes him to keep trying, to practice more, to take lessons, buy a new racquet, do just about anything in fact to have that happen again. Of course when he improves, the bar is just raised that much higher.

Some days we are particularly attuned to the subject matter, we just seem to see more clearly, it's easier to put the many elements of a photograph together and it's easier to recognize potential subject matter. A different day and you'd walk right by.

Myriad factors play here - sleep, stress, fitness, mood. Some days those ground strokes work perfectly, other times the brain just doesn't talk to the hand - welcome to real life.

Monday, January 29, 2007

Another Parkade Image

The lighting was harsh, bright sun, no clouds, a nice afternoon for anything but photography. This building was under construction (reconstruction?) and I liked the contrast between the warm colours seen through the building vs. the blue green glass covering the north wall. On screen at 100% you can see that the warm colours are in fact north facing brick walls lit by reflected light off south facing windows of other buildings.

Sunday, January 28, 2007

More From Parkades

Not a very productive day, just a chance to get outside and play with the camera. This image was handheld. DOn't know about you but sometimes the tripod is just too darn big - in this case the parkade had a concrete wall and I needed to be at the outside of it - no way for the tripod to get there so I leaned through the gap, and rested the camera on the concrete at one point, then held it tilted to aim it down and shot at 1/5 of a second, 17 mm. 17-40 lens. Of course, the 17 does minimize hand shake and having two of the three axes of rotation nailed by leaning the camera on it's L bracket meant that it was manageable.

Sometimes I'd like a really small tripod. RRS makes one but it's darned expensive for a one foot high tripod. I have spare ballhead so perhaps I'll simply rig something wooden up.

Saturday, January 27, 2007

Friday, January 26, 2007

The Candid Frame - Interviews

Andy asked what the link is to the Brooks Jensen interview - it's at The Candid Frame. Thanks to Howard for this link.

The Poison of Preconceived Ideas

The idea for this discussion came out of an audio interview of Brooks Jensen by I. Perrello. The latter made the point that children not burdened by knowing the history of photography and having no preconceived ideas of what a photograph should look like tend to be much more creative. Brooks made the point that without that knowledge it's difficult to move on.

I thought I'd discuss the more mundane issue of visiting a place that has been photographed before and the images seen by you. Hell, you might even have been the photographer. Assuming the images were good, how do you go about seeing it 'in a new light' (sorry)?

You could meditate, you could spend hours worrying about it, but here's some practical ideas for seeing differently.

1) approach the subject at a different time of day.

2) figure out what lenses were likely used and deliberately exclude the possibility of using those lenses - ie. if it looked like the images were shot with long lenses, see what you can do with wide...

3) Move in or move back - ie. opposite of what was done before.

4) If the previous images emphasized lines, how about concentrating on shapes.

5) If the previous images were sharp throughout - how about seeing what you can do with a good lens almost wide open.

6) Switch from colour to black and white or visa versa.

7) Look at what was emphasized in the previous images and see if there is another feature of the subject that could be shown.

8) If all the images were shot from eye hight, how about getting down on your belly for a good crawl round.

9) Even if there is only one thing to photograph and from one position, how about planning an image which looks radically different through changes in exposure and printing style.

OK, lets make it more challenging. Lets pretend you are creating a portfolio of images on a particular location, say the Badlands, and you have shot here before, need more images, want to keep the overall theme consistent, but definitely don't want 'deja vu all over again' images.

In this case you might well decide that part of that consistency is shooting with the same equipment, even the same lenses and in similar light. 10 pictures in soft light and two with high contrast probably won't work.

A new location would be ideal but if not available, how about walking through the scene from a different direction or at the opposite end of the day. If the previous images emphasized a certain type of curve, look for different lines, straight or zig zag. Deliberately switch from diagonals to horizontals. Consider broadening the definition of the portfolio to include another aspect of the badlands - say cactus or water, rain or snow. Even Ansel hasn't published a book of images of half dome only. After the first four or five, even he would have been stressed to make sufficiently different images to warrant a whole book on this one feature (striking though it may be).

Your project might be young women at a street corner - but how about adding some guys, or extending it to a variety of ages so one could compare facial expressions, dress style, postures, etc.

I thought I'd discuss the more mundane issue of visiting a place that has been photographed before and the images seen by you. Hell, you might even have been the photographer. Assuming the images were good, how do you go about seeing it 'in a new light' (sorry)?

You could meditate, you could spend hours worrying about it, but here's some practical ideas for seeing differently.

1) approach the subject at a different time of day.

2) figure out what lenses were likely used and deliberately exclude the possibility of using those lenses - ie. if it looked like the images were shot with long lenses, see what you can do with wide...

3) Move in or move back - ie. opposite of what was done before.

4) If the previous images emphasized lines, how about concentrating on shapes.

5) If the previous images were sharp throughout - how about seeing what you can do with a good lens almost wide open.

6) Switch from colour to black and white or visa versa.

7) Look at what was emphasized in the previous images and see if there is another feature of the subject that could be shown.

8) If all the images were shot from eye hight, how about getting down on your belly for a good crawl round.

9) Even if there is only one thing to photograph and from one position, how about planning an image which looks radically different through changes in exposure and printing style.

OK, lets make it more challenging. Lets pretend you are creating a portfolio of images on a particular location, say the Badlands, and you have shot here before, need more images, want to keep the overall theme consistent, but definitely don't want 'deja vu all over again' images.

In this case you might well decide that part of that consistency is shooting with the same equipment, even the same lenses and in similar light. 10 pictures in soft light and two with high contrast probably won't work.

A new location would be ideal but if not available, how about walking through the scene from a different direction or at the opposite end of the day. If the previous images emphasized a certain type of curve, look for different lines, straight or zig zag. Deliberately switch from diagonals to horizontals. Consider broadening the definition of the portfolio to include another aspect of the badlands - say cactus or water, rain or snow. Even Ansel hasn't published a book of images of half dome only. After the first four or five, even he would have been stressed to make sufficiently different images to warrant a whole book on this one feature (striking though it may be).

Your project might be young women at a street corner - but how about adding some guys, or extending it to a variety of ages so one could compare facial expressions, dress style, postures, etc.

Thursday, January 25, 2007

Cut And Run?

it struck me listening to Sam Abell, how much he makes his own luck by being in the right place then waiting for the last element to 'make' the image. This raises the more general question of how long do you wait for the light to change, the wind to die or the right combination of circumstances to happen, before getting frustrated or simply making the decision to 'cut your losses' and move on.

I find it a common scenario in landscape work. Some of the elements of a good photograph are there but the lighting isn't quite right. It might be an hour or more for the right light, it might be never. In that time that I spend waiting, I could be looking around for a different, possibly better photograph.

So how do you decide when to 'cut and run'?

Sometimes it's obvious - there's not a cloud in the sky and the odds of the lighting softening in the next hour has to be considered pretty darn low - maybe better to come back a different day.

Other times the odds of things improving approach 50% and if the chance of the image being really good is high, if only the light were right, then waiting makes good sense.

Sometimes I'll wait 10 minutes and if nothing happens, break down the camera and pack up - and of course sometimes that's just when you get that momentary break in the clouds and the light pours in or whatever. Many's the time I have maddly set up again, sometimes catching the light, other times not being ready.

The other strategy is one of setting up the camera and leaving everything in position, but then wandering around looking for another possible image. Sometimes this persuades me to move the camera, other times I will mark the spot by dropping my viewing rectangle.

Mathematically, it's a matter of statistics - the chance of the right circumstances happening to 'finish' this photograph are X over Y time. The image I'm waiting for is Z quality, while the possibility of a better image found elsewhere instead of waiting here is Zprime.

Now if only I could feed these numbers into my pocket calculator and it would tell me to make or break.

For now, I keep guessing and usually getting it wrong and occasionally specacularly getting it right, which compensates for all the wrong times and keeps up my optimism, not to say delusions.

I find it a common scenario in landscape work. Some of the elements of a good photograph are there but the lighting isn't quite right. It might be an hour or more for the right light, it might be never. In that time that I spend waiting, I could be looking around for a different, possibly better photograph.

So how do you decide when to 'cut and run'?

Sometimes it's obvious - there's not a cloud in the sky and the odds of the lighting softening in the next hour has to be considered pretty darn low - maybe better to come back a different day.

Other times the odds of things improving approach 50% and if the chance of the image being really good is high, if only the light were right, then waiting makes good sense.

Sometimes I'll wait 10 minutes and if nothing happens, break down the camera and pack up - and of course sometimes that's just when you get that momentary break in the clouds and the light pours in or whatever. Many's the time I have maddly set up again, sometimes catching the light, other times not being ready.

The other strategy is one of setting up the camera and leaving everything in position, but then wandering around looking for another possible image. Sometimes this persuades me to move the camera, other times I will mark the spot by dropping my viewing rectangle.

Mathematically, it's a matter of statistics - the chance of the right circumstances happening to 'finish' this photograph are X over Y time. The image I'm waiting for is Z quality, while the possibility of a better image found elsewhere instead of waiting here is Zprime.

Now if only I could feed these numbers into my pocket calculator and it would tell me to make or break.

For now, I keep guessing and usually getting it wrong and occasionally specacularly getting it right, which compensates for all the wrong times and keeps up my optimism, not to say delusions.

Just A Bit Of Colour For A Winter Day

Wednesday, January 24, 2007

Photographing By Instinct And First Impressions

Chuck talked about the difference between a snapshot and an work of art.

As for decisions and compromises in making a photograph, that's a great description of art vs. snapshot.

For the most part I agree with Chuck, but we do need to consider the times when an experienced (not to say wrinkled) photographer sees something in an instant, in it's total including boundaries and it's simply a matter of picking the right lens and pointing the camera at the scene.

I strongly support working the scene but am also amazed at just how often there is really only one right spot and that was the one you saw the scene from first. OF course, this makes sense, for if there is only one good vantage point, then unless you are in that spot, you aren't going to see the image and no light bulb going on. Having shot the light bulb image though, it's then time to work the scene and give the poor slob who's going to print a few more options. Probably you got the best shot but just maybe there's another arrangement that right now looks second best but once in the darkroom or on the computer, it turns out to be the stronger image.

Psychology research has shown that humans can process a scene in a spit second and long before any conscious thought about the value of a scene could be evaluated, we are in fact pattern recognition machines and an experienced photographer responds to interesting patterns in the midbrain rather than the cerebral cortex. You might say we are wired to respond to interesting compositions.

An inexperienced photographer responds to objects - that's a nice rock, a more experienced photographer to the rock sitting in front of the bush and behind the grass and with great clouds in the background and with that shadow reaching across. A really experienced photographer doesn't even think of it as a rock, he's seeing a light shape and a dark shape with intersting patterns and curves and the insubstantial like the shadow weigh as much in his glance as the more solid boulder.

As for decisions and compromises in making a photograph, that's a great description of art vs. snapshot.

For the most part I agree with Chuck, but we do need to consider the times when an experienced (not to say wrinkled) photographer sees something in an instant, in it's total including boundaries and it's simply a matter of picking the right lens and pointing the camera at the scene.

I strongly support working the scene but am also amazed at just how often there is really only one right spot and that was the one you saw the scene from first. OF course, this makes sense, for if there is only one good vantage point, then unless you are in that spot, you aren't going to see the image and no light bulb going on. Having shot the light bulb image though, it's then time to work the scene and give the poor slob who's going to print a few more options. Probably you got the best shot but just maybe there's another arrangement that right now looks second best but once in the darkroom or on the computer, it turns out to be the stronger image.

Psychology research has shown that humans can process a scene in a spit second and long before any conscious thought about the value of a scene could be evaluated, we are in fact pattern recognition machines and an experienced photographer responds to interesting patterns in the midbrain rather than the cerebral cortex. You might say we are wired to respond to interesting compositions.

An inexperienced photographer responds to objects - that's a nice rock, a more experienced photographer to the rock sitting in front of the bush and behind the grass and with great clouds in the background and with that shadow reaching across. A really experienced photographer doesn't even think of it as a rock, he's seeing a light shape and a dark shape with intersting patterns and curves and the insubstantial like the shadow weigh as much in his glance as the more solid boulder.

Tuesday, January 23, 2007

Sam Abell

I'd heard the name, knew he was a famous photographer but knew nothing about his work. One of the commenters at luminous landscape mentioned a workshop Sam tought so tonight it googled his name and came across this wonderrful find

Sam Abell Pictures and Video Interview

Check it out, there's a lot to be learned here, about working a scene, about light, about persistence, about returning when things are right and about a dedicated and skilled photographer. Highly recommended. And I'm going to go back to check out the whole site.

Sam Abell Pictures and Video Interview

Check it out, there's a lot to be learned here, about working a scene, about light, about persistence, about returning when things are right and about a dedicated and skilled photographer. Highly recommended. And I'm going to go back to check out the whole site.

Canon iPF 5000 # 2

Here's the link to the first entry on this new Canon >Printer. Aaron has pointed me to the user information site for the 5000 here which looks like it is going to be extremely useful.

The latest adventure is that I note a yellow tone to warm black I don't like so I have switched back to neutral black which has a selenium toned look to it which is subtle and just right.

I am noticing some lines on part of the print. It might be banding but in fact I suspect I'm getting some head contact as it's too broad for banding and it disturbs the surface of the paper. I'm going to see if I can adjust the head position or increase vacuum or do both.

I'm getting used to confirming size and type of paper for every single manual feed sheet of paper so I don't think I would consider that a major flaw in the printer, and besides, the manual top feed is much easier than the Epson. The paper drops in until it comes against a definite stop. In addition, there is mobile guide that lines up the left side which the 4000 didn't have, and unlike the Epson you don't have to push the paper in against fair resistance before coming up against the final stop which with the initial resistance was difficult to find.

Some sheets are getting misfed - ie. they go in just fine but the printer says they are squint. The good news is this so far is happening about as often as on the 4000, which is to say, too often, but changing the paper is much simpler than on the 4000, push the up arrow and remove the paper. On the Epson you had to release the lever, wait interminably, then refeed, hoping you waited long enough.

So far the bottom line is it has the possibility of being an awesome printer but initial teething problems will need to be solved and so far I cannot recommend it until that happens. I will keep you posted.

The latest adventure is that I note a yellow tone to warm black I don't like so I have switched back to neutral black which has a selenium toned look to it which is subtle and just right.

I am noticing some lines on part of the print. It might be banding but in fact I suspect I'm getting some head contact as it's too broad for banding and it disturbs the surface of the paper. I'm going to see if I can adjust the head position or increase vacuum or do both.

I'm getting used to confirming size and type of paper for every single manual feed sheet of paper so I don't think I would consider that a major flaw in the printer, and besides, the manual top feed is much easier than the Epson. The paper drops in until it comes against a definite stop. In addition, there is mobile guide that lines up the left side which the 4000 didn't have, and unlike the Epson you don't have to push the paper in against fair resistance before coming up against the final stop which with the initial resistance was difficult to find.

Some sheets are getting misfed - ie. they go in just fine but the printer says they are squint. The good news is this so far is happening about as often as on the 4000, which is to say, too often, but changing the paper is much simpler than on the 4000, push the up arrow and remove the paper. On the Epson you had to release the lever, wait interminably, then refeed, hoping you waited long enough.

So far the bottom line is it has the possibility of being an awesome printer but initial teething problems will need to be solved and so far I cannot recommend it until that happens. I will keep you posted.

Monday, January 22, 2007

Decisions and Compromises

It's rare for a scene to perfectly unfold, with obvious boundaries for the framing of the image and a single position being clearly the strongest. In my experience, what happens in the real world is that if I move left, that rock shows nicely but then I have that problem with the bush, if I move right, the bush is hidden but I lose the curve of the rock, and so on it goes, one compromise after another. Sometimes the compromises are such that you have to walk away, or at least that image doesn't get used. Other times there is a solution which results in a strong image, and rarely there is the image that just requires no such decisions, there is one right way, it is uncomprommised, it's obvious and you are off and running.

So this raises some questions.

DO great images only come from images which didn't need compromises?

Would a different photographer have more or less trouble making the right decisions?

Is there something we can do to help the process of making decisions?

Is there a difference between the 4X5 shooter who with 12 shots for the day has to decide once and for all which is the best shot versus the digital shooter who at least in theory can take every single possible compromize and sort out later which one is actually better?

It's my impression that great images do not in fact uniquely come from images which don't involve compromises. We will never know how much 'good stuff' existed beyond the borders of the print. We don't know if had the photographer been able to move to the left six inches, something wonderful would have been added, all be it at the cost of adding something distracting. Since this is already a great image, it doesn't really matter. We don't look at the Mona Lisa, and say to ourselves, if only she had bigger breasts, or a longer nose or whatever. We're looking at a piece of art, not arranging a 'hot date'.

It's almost a given that someone else might have an easier time making the decisions on what's best. We know for ourselves, some days we can make those decisions quickly and confidently, other days in similar situations we are indecisive, so it would seem reasonable that there be differences between photographers. It may be easy for a beginner to make the image since he's not even aware of the subtle elements about which the more experienced photographer is agonizing. It seems that like in life in general some of us are more confident in our decisions, rightly or wrongly.It's more than possible that the photographer who couldn't decide and gave himself two negatives to choose from will be the one returning with the great image.

I would argue that more images are spoiled by the addition of a distracting element than by the elimination of something nice, so all things being equal, it's better to go with the 'lesser is better' image. I find it frustrating to leave in the distracting element, persuade myself it won't matter, be excited about the image, then to be disappointed when I realize that it truly won't work with the distracting element present - no matter how I crop the image, no matter what printing tricks I use to 'tone it down'.

To be fair though, one needs to remember that elements may be distracting because they stand out from the picture in a 3D world. Perhaps with one eye closed, the element isn't distracting at all. Perhaps the element is distracting largely because of it's colour or brightness and sometimes these can be corrected in the printing.

I do wonder if the use of a large screen pocket digital camera (there are some with three inch screens and black and white modes and a zoom lens) wouldn't make an ideal viewing tool which would help in the decision making process.

So this raises some questions.

DO great images only come from images which didn't need compromises?

Would a different photographer have more or less trouble making the right decisions?

Is there something we can do to help the process of making decisions?

Is there a difference between the 4X5 shooter who with 12 shots for the day has to decide once and for all which is the best shot versus the digital shooter who at least in theory can take every single possible compromize and sort out later which one is actually better?

It's my impression that great images do not in fact uniquely come from images which don't involve compromises. We will never know how much 'good stuff' existed beyond the borders of the print. We don't know if had the photographer been able to move to the left six inches, something wonderful would have been added, all be it at the cost of adding something distracting. Since this is already a great image, it doesn't really matter. We don't look at the Mona Lisa, and say to ourselves, if only she had bigger breasts, or a longer nose or whatever. We're looking at a piece of art, not arranging a 'hot date'.

It's almost a given that someone else might have an easier time making the decisions on what's best. We know for ourselves, some days we can make those decisions quickly and confidently, other days in similar situations we are indecisive, so it would seem reasonable that there be differences between photographers. It may be easy for a beginner to make the image since he's not even aware of the subtle elements about which the more experienced photographer is agonizing. It seems that like in life in general some of us are more confident in our decisions, rightly or wrongly.It's more than possible that the photographer who couldn't decide and gave himself two negatives to choose from will be the one returning with the great image.

I would argue that more images are spoiled by the addition of a distracting element than by the elimination of something nice, so all things being equal, it's better to go with the 'lesser is better' image. I find it frustrating to leave in the distracting element, persuade myself it won't matter, be excited about the image, then to be disappointed when I realize that it truly won't work with the distracting element present - no matter how I crop the image, no matter what printing tricks I use to 'tone it down'.

To be fair though, one needs to remember that elements may be distracting because they stand out from the picture in a 3D world. Perhaps with one eye closed, the element isn't distracting at all. Perhaps the element is distracting largely because of it's colour or brightness and sometimes these can be corrected in the printing.

I do wonder if the use of a large screen pocket digital camera (there are some with three inch screens and black and white modes and a zoom lens) wouldn't make an ideal viewing tool which would help in the decision making process.

Sunday, January 21, 2007

Mash Vat

Mash pours into the fermenting vat. Once full, it starts to bubble with CO2 as the sugars in the grain are converted to alcohol and CO2. In fact, the CO2 lies so heavily over the vats that anyone falling in would die before reaching the side. I had thought they cooked the mash but in fact the special yeast cultures don't work well at higher temperatures and those are cooling tubes seen at the bottom of the vat.

Saturday, January 20, 2007

Crane Museo SIlver Rag - Oh So Close

I have been having problems with my Epson 4000 and prints are getting marked with black lines on either side of the image from a dirty head. I have been wanting to try a printer which could do the new semi gloss papers and last week broke down and purchased a Canon IPF5000 printer. My local camera store stocked both Hahnemuhle Pearl and Crane Museo Silver Rag and I preferred the surface of the Silver Rag - slightly glossier, slightly more textured and the texture appeared random while the texture on the Pearl is slightly cloth like, all be it very fine.

My very first print from the 5000 in monochrome was good, the second one excellent with a quickly adjusted tone curve and everything else at default. Two problems occurred with the Silver Rag. Firstly the paper is so thick and slightly curved that the edges catch on the print heads as they go back and forth - you can sometimes hear it and you can certainly see the frayed edges after printing. I figured I'd eventually understand how to adjust for paper thickness, though confess I haven't done so so far. The second problem was of more concern. Each and every print had what appeared to be a water mark on it - a circular area that was dull in surface. Some prints had one, others had half a dozen. They appeared to be at random locations and varied in diameter from 3 - 5 mm.

It didn't take me long to have a look at the paper before it went into the printer and there were the spots, right on every single sheet in the box. Subsequently I opened the second box I'd purchased when I returned the paper to the store, and it too had the same 'water' spots.

I have replaced the paper with Hahnemuhle Pearl but my original impressions still hold - I prefer the surface of the SIlver Rag.

I have contacted Crane and I'd like to think the problem will get solved.

I intend to order some of the Innova paper (can't be bought here directly in Calgary and no Canadian distributer) but the last time I tried I didn't know the same paper surface F came in both matte and glossy - of course I got the matte. My luck!

As regards the black and white images the printer can make - it's superb. I haven't given it a full check yet and will report back on quality as I try more prints and inspect them in various colours of light, but so far I like the printer.

Why I have to specify the paper type and size for every single hand fed sheet, even though they are all the same size, is beyond me. Michael Reichmann indicates a new version of the firmware is coming out soon, we can hope.

On the issue of bronzing. With the Canon printer and both the Hahnemuhle and Crane papers, the dark inks don't sit on the surface like they do with older printers. On the other hand, the inks on the Canon are more glossy than the paper and this means that light areas of the print don't have as much gloss so there is some surface differential (the opposite of bronzing?).

The only way round this would be the way that the new HP 3100 printer is doing it and that is with a gloss optimizer. Essentially a print varnish that is applied over the entire image. I don't have a 3100 (not that I wouldn't like one) but my experience with the R800 printer which also uses gloss optimizer is that it completely solves the differential surface problem. On the R800 at least however, the varnish does slightly grey the white of the paper. It can be seen where white parts of the image touch the image border. With the R800, the gloss optimizer isn't applied to the entire surface of the print, just to where the image is.

The other way around this would be to use Premier Art Shield Spray or something like it. I have absolutely no experience using it but suppose it's something equivalent to artists acrylic gloss medium which is basically a glossy acrylic varnish.

This raises questions about overspray, fumes, fineness of spray, nozzle clogging, air brushes, print drying, dust sticking and other fun issues. I see that Hahnemuhele actually recommends spraying their prints for longivity. What does that mean?

Anyway, the adventure continues.

Oh, the image above is part of my drums series, three images differentially focussed and blended with Helicon Focus, converted to black and white in Photoshop (there wasn't a lot of colour to filter), and substantial dodging and burning. I used Akvis Enhancer on the image with considerable advantage.

Grain Bins

Thursday, January 18, 2007

Phot'Art Magazine

I think it was The Online Photographer who recommended Phot'Art Magazine. My first three issues have arrived and I am very impressed. Printed on heavy semi matte paper the printing is excellent. It's not up to the standard of Lenswork but few books never magazines are, but the colour work is superbly reproduced and the black and white is good. There are a variety of styles and categories of photographs from landscape to fashion, advertizing to flowers. The text is split English and French so you don't even have that issue.

So far they seem to be emphasizing a single country in each issue, China and Italy in the two I have looked at so far.

I think it's a really good idea to see how subjects are treated in other parts of the world and by different cultures.

In landscape photography there is a lot less emphasis on capturing every detail with a large format camera and more on the mood in which grain isn't a problem and can even be helpful.

So far they seem to be emphasizing a single country in each issue, China and Italy in the two I have looked at so far.

I think it's a really good idea to see how subjects are treated in other parts of the world and by different cultures.

In landscape photography there is a lot less emphasis on capturing every detail with a large format camera and more on the mood in which grain isn't a problem and can even be helpful.

Getting Past the Object

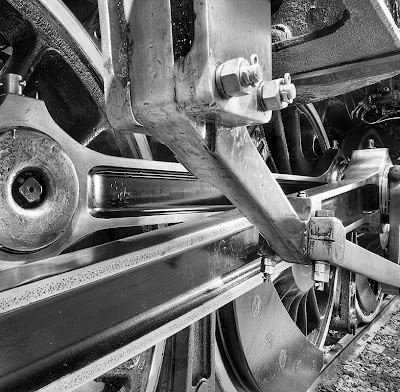

Some time ago I was photographing 2816, a steam engine, and the loved and polished locomotive had a wonderful sheen off of the drivers and other paraphenalia of the piston to wheels mechanisms. I took more than a dozen pictures and even picked a couple that looked nice to show. I have 'thumbed' through the image in Photoshop Bridge a number of times but this morning, instead of seeing pictures of 'drivers', I saw patterns and shapes and recognized that the centre of one of the images might work as an abstract.

I think this ability to see beyond the object and look at it in terms of shapes, shadows, lines, curves and edges is extremely important. Even when a photograph is quite literal - a picture of a mountain, for example, if you can see past the mountain and think of it in the above terms, composition is likely to be stronger.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)